6 hours ago

About sharing

During World War Two, hundreds of thousands of people were held against their will. Service personnel captured in conflict became prisoners of war, and civilians were confined in internment camps if they were believed to be a threat to the state.

The exploits of the people who managed to physically escape are often well-known, their extraordinary stories immortalised in film, literature and public memory.

But lesser known are the people who also found a path to a form of escape, but within their own minds.

From patchwork quilts to an orchestra of humming women, a dogged dog to drawings of imaginary aircraft – here are some of the extraordinary stories forming part of an exhibition at the National Archives in Kew.

The art of survival

Ronald Searle is now best known for his creation St Trinian’s – a comic strip revolving around the mayhem and juvenile delinquency of a girls’ school.

Mr Searle was a prisoner of the Japanese in World War Two – first in Changi Prison and then in the Kwai jungle, working on the Siam-Burma Death Railway.

He suffered dysentery, beriberi, ulcerated skin and repeated bouts of malaria. Yet he held an unwavering desire to document the things he saw.

In his book To The Kwai and Back, he describes his desire to draw as a “mental lifebelt”.

“Frequently, it seemed a stupid waste of what little energy I had left to continue drawing for no other reason than that of carrying out my self-appointed task of recording what I could of what was going on,” he wrote.

“It was often very hard to force myself to continue when all I wanted was to forget and escape into the reality of sleep”.

It was a dangerous hobby – if any of the Japanese soldiers found his work, he would have been killed.

Searle was only 25 when he arrived back in the UK in October 1945, in possession of about 300 drawings.

Olga Morris

Nine-year-old Olga Morris and her family lived in Malaya before the Japanese invasion and though they tried to make their escape by ship, they were captured in Singapore and interned in Changi camp.

They had to walk 18 miles without water, which she remembered clearly: “We had to go over a bridge. There were nine heads on this bridge, all on spikes. I can still see two of them.”

At the camp there was little food and the guards vigilant and cruel. Nearly everyone was unwell with infections and sores.

But one of the internees decided to start a Girl Guide group, which would meet once a week in a corner of the exercise yard.

As a surprise birthday present for their guide leader, the girls met in secret and sewed her a patchwork quilt using scraps of material they had found, including pieces of rice bags.

Airman, Painter, Forger and Spy

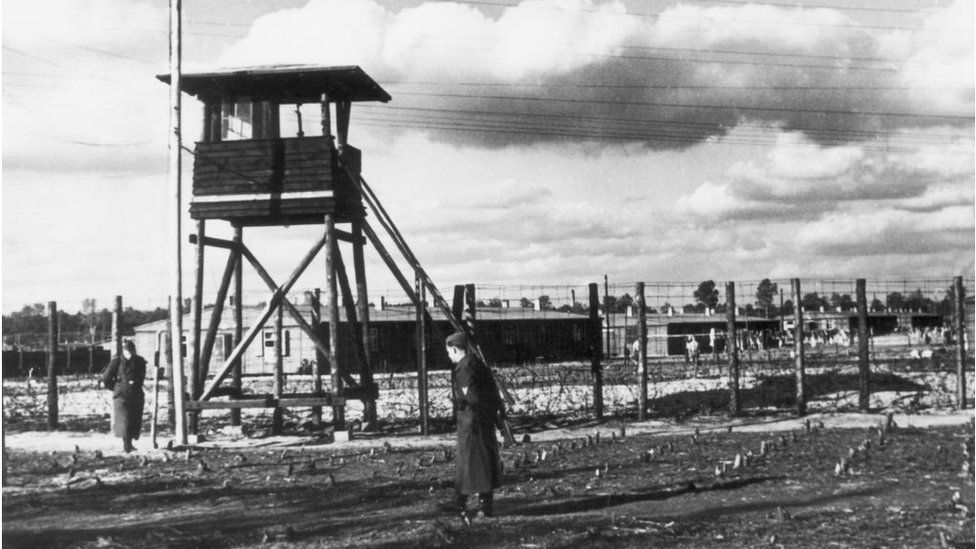

Guy “Griff” Griffiths, a Royal Marine pilot, was one of the first naval officers to be captured by the Germans.

He was held at camp Stalag Luft III – the setting of the 1963 film The Great Escape – and found distraction from captivity by feeding misleading intelligence to the German authorities.

He was an accomplished artist and his skills as a forger were useful in producing false paperwork for other POWs.

He would also draw fake Allied aircraft and leave the pictures lying around for the guards to find.

Griffiths was also in contact with MI9 (British Military Intelligence Section 9) – his letters to the Royal Marines Corps’ magazine contained encrypted details about camp personnel.

Judy

Leading Aircraftman Frank Williams formed a strong bond with English Pointer Judy, a Royal Naval ship’s dog he encountered in an Indonesian camp.

Judy became the only animal to be given the official status of prisoner of war.

Frank managed to hide his canine companion from prison guards, and although they became separated, they were reunited.

He said: “A scraggy dog hit me square between the shoulders and knocked me over. I’d never been so glad to see the old girl. And I think she felt the same”.

Frank and Judy, along with their fellow POWs, spent a year cutting through the Sumatran jungle, opening a route for a new railway.

After the war, Judy was smuggled on board a ship and hidden for the majority of the six-week journey to the UK.

She then spent six months in quarantine in London before being reunited with Frank, who was permitted to take her with him on his new Royal Air Force duties in the UK.

Judy and Frank lived in Portsmouth and then in Tanzania, where Judy died on 17 February 1950. She was buried with an RAF jacket.

Margaret Dryburgh

When Singapore fell in 1942, missionary and teacher Margaret Dryburgh tried to escape from the advancing Japanese forces by ship, but was captured.

Taken to a Japanese internment camp at Sumatra, she and fellow internee Norah Chambers set up a vocal orchestra.

The women did not attempt to imitate instruments but instead used humming for sounds and consonants to obtain a sense of rhythm.

Ms Dryburgh also composed the music and words of The Captives Hymn. It was sung in camp every Sunday – and is now sung around the world.

Ms Chambers later said: “Our vocal orchestra was silenced forever when more than half had died and the others were too weak to continue…it was wonderful while it lasted.”

The exhibition runs until 21 July. It is free to visit.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk